By Nasser Aldhaheri

Before my university graduation, I chose a subject that was then the talk of the press in the UAE, the threats to national identity, as a final project, especially after a series of bizarre crimes had surfaced—crimes like child harassment, murders, attacks on homes, assaults on European wives behaving naturally before a tough labor community.

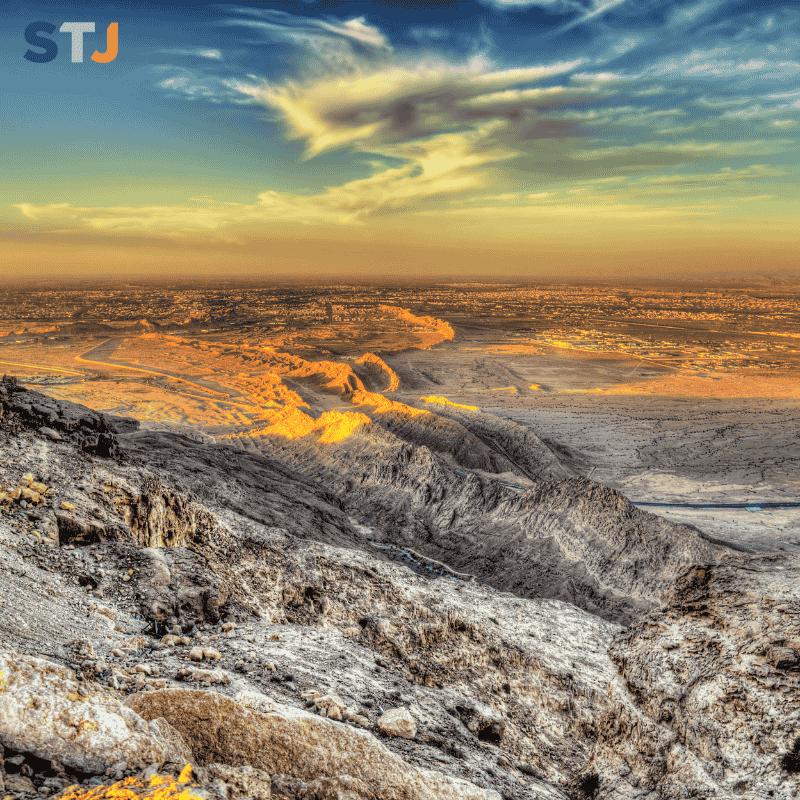

In the city of Al Ain, this oasis of greenery surrounded by dunes, with gardens and water channels, stands majestically. To its east and south extends Jebel Hafeet, rising to 1,250 meters above sea level, concealing archaeological sites and ancient tombs within its caves, home to wild gazelles, ibex, mountain goats, and foxes.

Flocks of Afghan workers moved nearby, as the environment resembled their homeland—mountains, independence, and simplicity. As the city’s construction and infrastructure development flourished, the influx of workers from across the world increased, especially Afghans, who began to form a small community near the mountain’s edges, sometimes hidden from the eyes of authority, living by their customs and tribal traditions, outside the reach of regulations.

This settlement grew into an essential hub, led by a notable leader who looked after their affairs, establishing a mutual aid fund for those facing hardships. They created their own Afghan town.

That alley was a community within a community, ruled by unwritten laws and customs beyond the reach of official decree—laws.

I was filled with doubt, especially after hearing the tales and stories whispered among the people: that the criminal could escape to the mountain, elusive and hard to catch; that illegal migration through the endless desert borders was dangerous and exhausting.

It was nearly impossible for me to enter that zone; it was almost forbidden territory for anyone who wasn’t a resident or known to the community. Yet, I devised a clever plan with some colleagues from my graduation project: we went under the pretense that one of us was a senior official at the municipal authority, coming to see for himself how a large mosque could be constructed for the community to perform the five daily prayers together. We faced some opposition, but reluctantly, they allowed us limited photography—just enough to capture the proposed mosque’s space

I found myself torn between my duty as an investigative journalist and the ethics of portraying people—many of whom probably harbored good intentions, seeking work and livelihood—and a minority perhaps involved in illegal activities. My social responsibility towards the community of Al Ain, and my loyalty to my country, pressed me to consider whether this place was armed. Those who smuggle drugs, hashish, or weapons would certainly feel the need to be armed to protect their trade. But what if the smuggling also involved weapons?

I decided to avoid mentioning names or photographing individuals. My focus would be solely on the actions, movements, mechanisms, and atmosphere of the place. Based on this, I could draw conclusions from the diverse and tangled scenes, and from analyzing their responses to my questions.

My questions hovered over general topics: what is the name, and what does it mean? How long have they been there? Do they love the place? What do they do? Are they earning enough to support themselves and their families? Do they stay in touch with their relatives back home? How many times have they traveled back to their countries over the years? And what do they dream of—to live happily?

Fear was always ahead of us, lurking behind every step. We could’ve been caught at any moment. The Afghan people do not tolerate suspicion or deception—they see it as betrayal, a violation of trust. That was how I read the morals of mountain men.

And when the story was published in the newspapers, after much refinement, it remained mostly humane on the surface, carefully avoiding targeting specific individuals or particular nationalities. Yet, beneath the polished surface and within the subtle manipulations of language—understanding that some authorities may grasp—the piece served as a warning bell. The place was on the brink of explosion—perhaps tomorrow, or next month, or after years.

Guilt gnawed at me because I was not entirely honest or transparent with those people. Still, I had been truthful with my community, and given the sensitivity of the topic, I prioritized the collective reconciliation over individual interests. I chose service over harm—to serve the community rather than cause its ruin.

That conviction hung in the balance until a different kind of morning broke over the city—one far removed from the usual dawns I knew—after dawn prayer, morning coffee, and neighborly chatter. It was a loud, chaotic morning—protests, madness in the streets, gunshots echoing in the air, and news of innocent lives lost—tragic, the fury unleashed from the Afghan alleyway, sweeping toward the tranquil city center, toward a law that would regulate their lives, foster forgiveness, love, coexistence, and peace.

From that first, pivotal experience in the journalism, I learned that some important topics demand courage—to look into the future, to dare to say: “I am here… to make a difference.”

This article is part of the practical work carried out by the students of the Master’s in Travel Journalism.